We talk a lot about intrinsic and extrinsic value here on the site, especially when it comes to event risk and trade management after the fact. I wanted to go a little more in depth on the subject because I’ve always felt that understanding intrinsic/extrinsic premium is when the first big light bulb goes on for those learning options. The first few paragraphs may seem remedial if you’ve been trading options for years but it’s important to have before we start to tie it all together with earnings.

Let’s start with terms we use “in-the-money” and “out-of-the-money” and how that relates to intrinsic and extrinsic value.

An in-the-money option has intrinsic value. In the case of a call, the strike is lower than where the stock is trading (e.g. stock is trading 55, so the 50 call is $5 “in the money”). In the case of a put the strike price is higher than the the stock (e.g. stock is trading 55, so the 60 put is $5 “in the money”). The biggest thing to remember is that these in-the-money options are intrinsically worth something right now… even if the stock stopped trading until expiration. (If the option price equals the intrinsic value, an option is considered to be trading at parity.)

Out-of-the-money refers to options whose strike price, in the case of calls, is higher than the stock (e.g. stock is trading 55 , so the 60 calls are $5 out of the money). In the case of puts, it is out of the money if the put strike is below the stock price (e.g. the stock is 55, so the 50 puts are $5 out of the money).

Out-of-the-money options have no intrinsic value. But they have value. And in-the-money options trade for more than their intrinsic value. That additional value that can’t be explained by the intrinsic value of the option is extrinsic value. Extrinsic value is everything in options trading. It can seem more complicated than it is and can scare off the faint of heart. But it shouldn’t scare you and understanding it is the key to using options properly in your account.

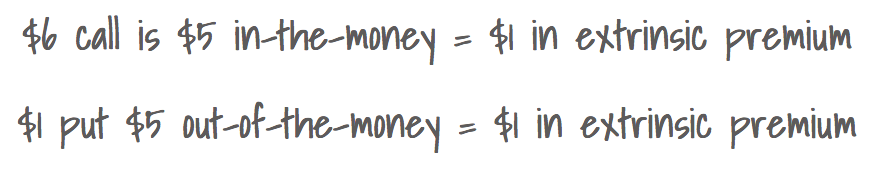

Going back to our $55 stock, let’s look at the 50 strike calls and puts and give them values. Let’s say the 50 calls are trading $6 and the 50 puts are trading $1.

Notice anything?

The $6 dollar calls are intrinsically worth $5, but they trade at $6. That extra dollar is the extrinsic value and is represented in the entirely extrinsic value of the corresponding 50 puts, as $1:

A lot of factors go into the extrinsic premium, time to expiration, implied volatility, dividend, carrying cost and short interest. But it can be boiled down to this, it’s assigning a value to the predicted movement of the stock between now and the expiration of those options.

In other words, you want to buy a put to protect your shares $5 below where the stock is trading? That’s going to cost you $1. Would you prefer to buy an in the money call to define your risk down to $50 vs owning the stock at $55 with unlimited risk? that’s going to cost you an extra $1, essentially raising your breakeven on the stock by that $1 amount.

That dollar of extrinsic premium decays over time as the days until expiration (and therefore the amount of time for a stock to move) decrease. The other main factor on its pricing is the implied volatility input, basically telling that extrinsic premium how much to expand or contract based on assumptions of future movement and demand by buyers and sellers of the options themselves. That $1 becomes $2? It means there’s demand for options based on assumptions (or worries) about that stock moving more than previously assumed. That $1 becomes $0.50? That means the opposite, the days until expiration are getting shorter and/or people are selling options based on an assumption that no big stock moves are expected.

Make sense?

Ok, so with earnings season in full swing let’s apply that to some event trading. As I discussed a few weeks ago it often looks like implied vol is rising into earnings. But more often than not, that is implied vol that has been high gradually being accounted for more in 30 day forward looking averages. (read more on that here) It’s not like the earning dates sneak up on anyone and they have to rush out to buy puts and calls at the last minute. The dates are generally obvious as to which expiration month they will fall, and those months start (as soon as they’re listed) with implied vol higher than surrounding months. (changes in assumptions about that earnings implied move is another story, and see make vol rise and fall into the event as options traders get worried or giddy).

But as I said in that original post, what is real is the collapse of implied vol after the earnings event. Much of the extrinsic premium of options into earnings is priced to be gone after earnings. It’s quite obvious why. After the initial event move, the uncertainty of the event is gone. The stock will have established a new baseline and investors have the freshest available information to buy or sell accordingly from that new spot. The information gap between investors and the company itself is close to zero at that point. That gap will then start to slowly build up overtime and reach a crescendo once again 3 months from now as investors have to guess and management has to wait to release what they know.

And that’s what the extrinsic premium of options is pricing into an earnings event. That information gap between management and investors. In general, when the investor is buying options at a high level volatility, they either buying insurance, or straight up gambling. In aggregate, the math is against them.

Think of it this way. If you bought a stock into earnings, you have a 50/50 chance of making or losing money. However, unlike a coin flip where a winner takes the penny and a loser loses the penny, it is unknown how much money will change hands after the coin flip. It’s a binary outcome with non binary results.

Therefore, people look to define their risk in the options market. But that comes with a big trade-off as not only do they have to pay for the ability to define risk (in the form of extrinsic premium), which means that they’ve now lowered their odds of success on a binary scale below 50%, but they are doing so at the worst possible moment into earnings to buy that extrinsic premium, as it’s priced to lose a significant chunk of its value after the event (making a less than 50% chance even worse). That misunderstanding can be compounded when a novice trader decides that any of that fancy math can be overcome by just being right in bigger size. That’s the danger of options being used simply for gambling leverage.

Understanding this relationship between event risk and extrinsic premium is key to understanding options. It’s the reason why professional options traders tend to be net short premium. It’s far easier to make money selling insurance than buying insurance.

And you don’t need to be an options market maker to avoid some of the novice errors of event trading. If your desire is to define risk, either in the form of a hedge or a stock alternative, understand that relationship between intrinsic premium and extrinsic premium. On a hedge, try to make it zero cost or as cheap as possible by selling an upside call versus a put spread. In the case of a stock alternative, don’t just buy a call or an out of the money call spread on the chance you may be right on direction. Think about those less than 50% odds and how it relates to the profits you’ve already made in the stock. Is that trade-off worth it? And when possible, try to have the math on your side. One example is an in the money butterfly that we feature on RiskReversal, where the intrinsic breakeven is better than the stock entry, and a collapse of implied volatility on the the position is actually in your favor after the event.

All of these things have tradeoffs, most short premium trades require you to flip the risk/reward scenario on its head, instead of risking 1 to make 4, you may be risking 4 to make 1, but with much greater odds of any success. An in-the-money call butterfly may be risking 4 to make 6 and actually has risk of losing money if the stock goes above the short strike, whereas a call spread may be risking 2.50 to make 7.50, and has no risk of losing money if the stock is above its short strike. But that in the money fly has much greater odds of success, while having defined risk. That non-binary relationship between risk and reward is the key difference between stock and options.

Obviously adding more strikes to a simple call or put buy makes things seem more complicated. But by understanding extrinsic premium, and how to protect yourself or benefit from its collapse out of earnings (and its decay over time) you’ve made options trading way less complicated and hopefully more rewarding for your portfolio.